Guest Writer: Ian Johnson, Registered Patent Agent, Plant & Planet Law Firm

Introduction

Over the past two decades, cannabis has seen increasing public approval, reflected in legalization of medical and recreational marijuana at the state level and federal legalization of industrial hemp. As cannabis and related industries expand, participants are expected to seek competitive advantages, including patent protection. This report examines trends in United States patent filings and issuances related to cannabis since 2000.

While cannabis legalization has been slowly occurring since the 1990s, a significant development was the legalization of recreational marijuana in Colorado and Washington in 2012. Since then, several other states have followed in opening up recreational markets. Therefore, particular attention is given to activity since 2012, as the existence of recreational markets presumably creates greater competition and greater desire to obtain intellectual property protection. This date also conveniently overlaps with the beginning of implementation of the America Invents Act (AIA), which significantly altered the United States patent system. While changes in patent practice post-AIA are beyond the scope of this report, it is useful to examine behavior year over year from 2012 onward to see if legalization has resulting in increased patent activity.

Summary of Findings

Patent activity related to cannabis has increased significantly over the last decade. Filings of cannabis-related patent applications increased 96% between 2012 and 2019, with filings related to recreational and medical cannabis increasing 257% over the same time. The data show that legalization had a demonstrable effect on cannabis patent activity, and that significant resources are being invested in patent protection in the personal use sector of the cannabis industry. These trends are expected to continue, and industry participants should consider this when making decisions regarding business models and intellectual property protections.

Methodology

Research was performed using the LexisNexis Total Patent One database. Results were limited to United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) publications. The following search terms were used:

- cannab* – use of the wildcard * returns results for cannabis, cannabinoid, and other variants

- mari?uana – use of the wildcard ? returns results for marijuana and marihuana

- tetrahydrocannabinol

- hemp

The listed terms were searched in the title, abstract, or claims of issued patents and printed publications. Searches were limited by time periods as shown in the detailed results. A complete list of all returned documents was created. Because of the structure of the data, a patent could create multiple documents: an issued patent and one or more published applications. For year-over-year results, these duplicates were not removed. This is not considered significant, as publication of an application and issuance generally occur in different years so double counting is minimal. However, duplicates were removed in calculating the number of filings each year to avoid inflation of filing numbers.

Detailed Findings

Overall Cannabis Patent Trends

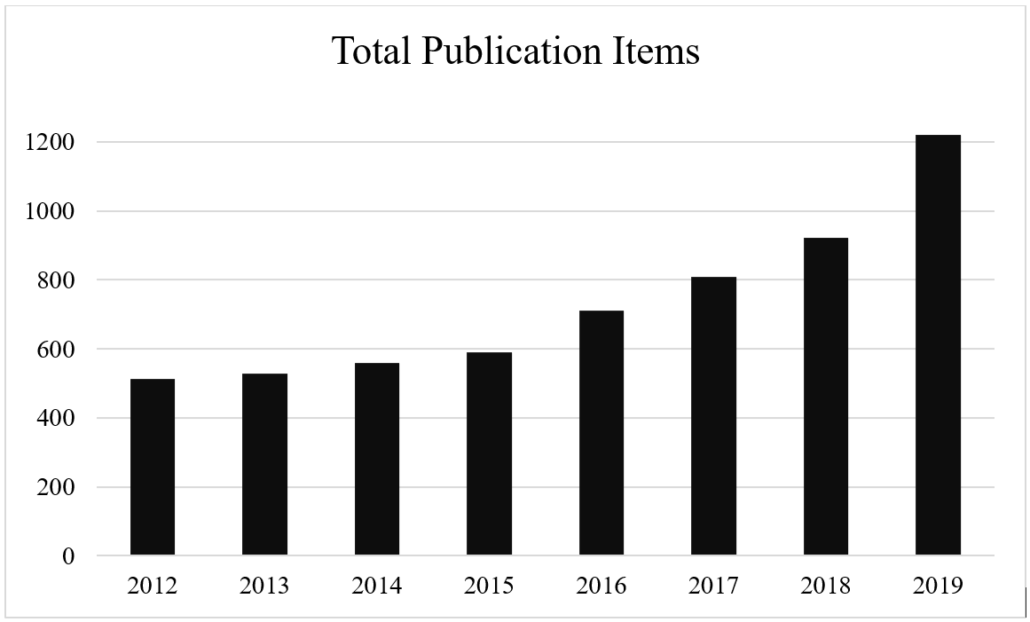

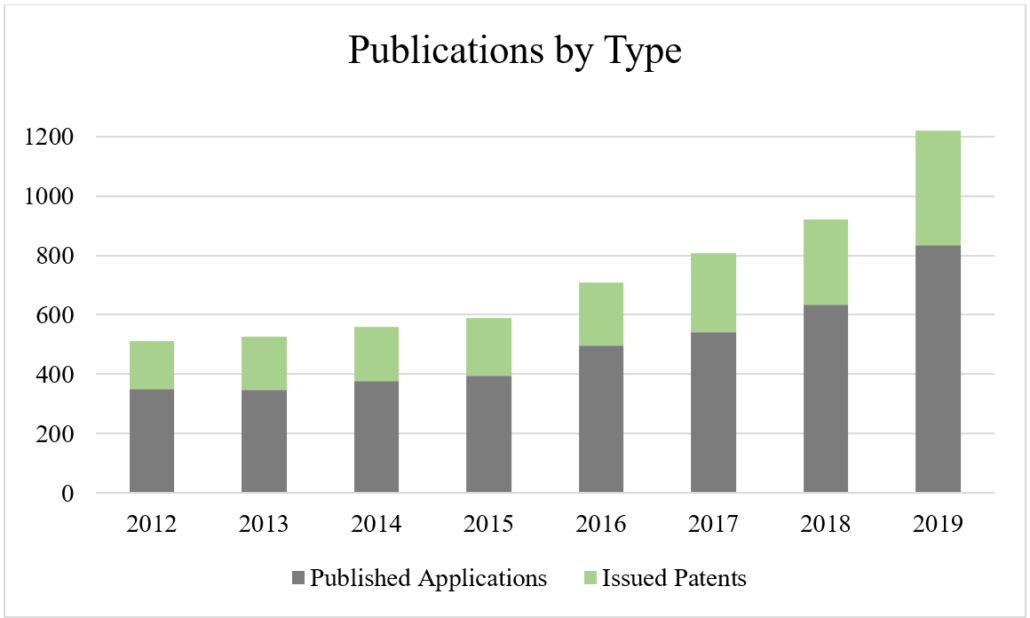

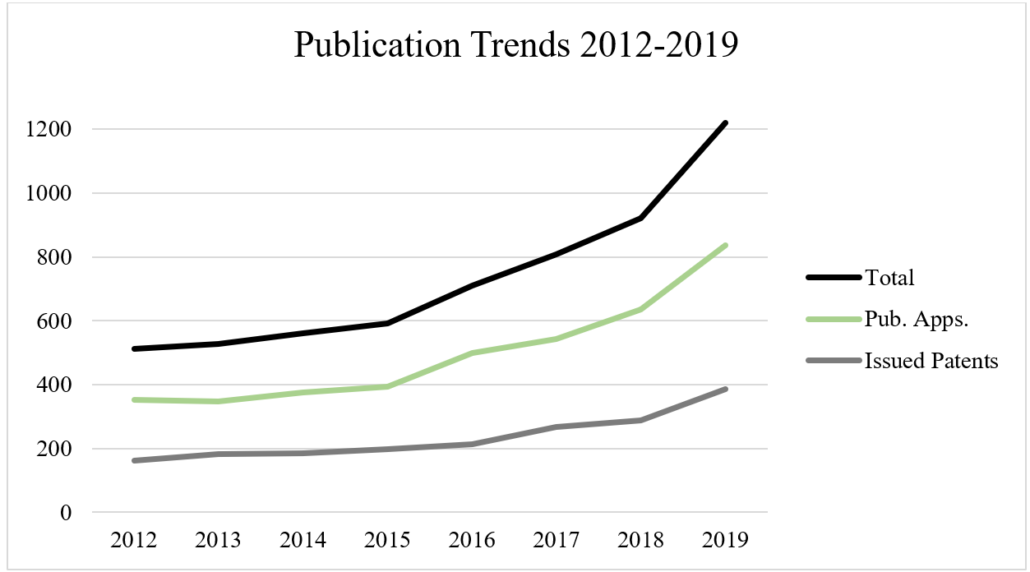

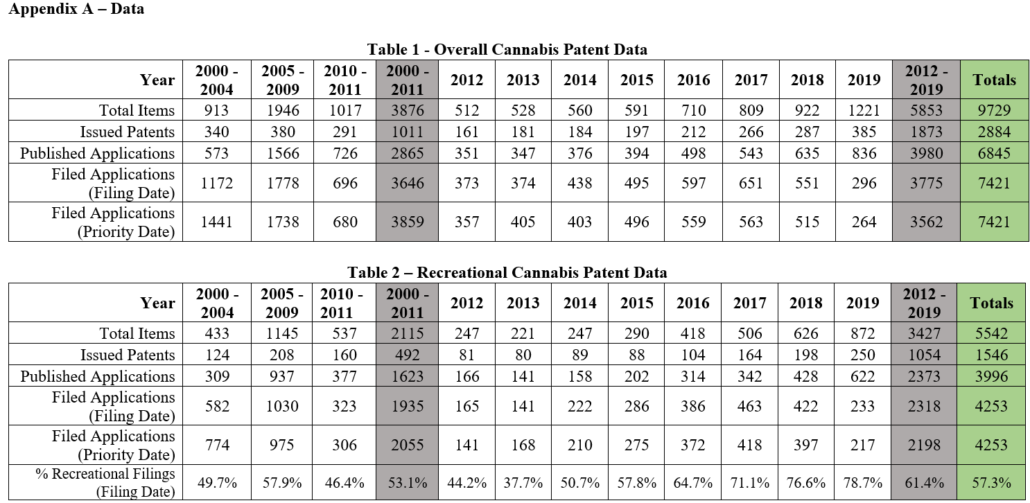

Cannabis patent activity has increased notably since 2012. Between 2000 and the end of 2011, the USPTO published 3876 documents concerning cannabis inventions. This number consisted of 2865 published applications and 1011 issued patents. Between 2012 and the end of 2019, the USPTO published 5853 documents, consisting of 3980 published applications and 1873 issued patents. This represents 51% more total documents in 2012-2019 compared with 2000-2011. Publications increased year-over-year since 2012, with a 138% increase between 2012 and 2019. The charts below demonstrate this trend.

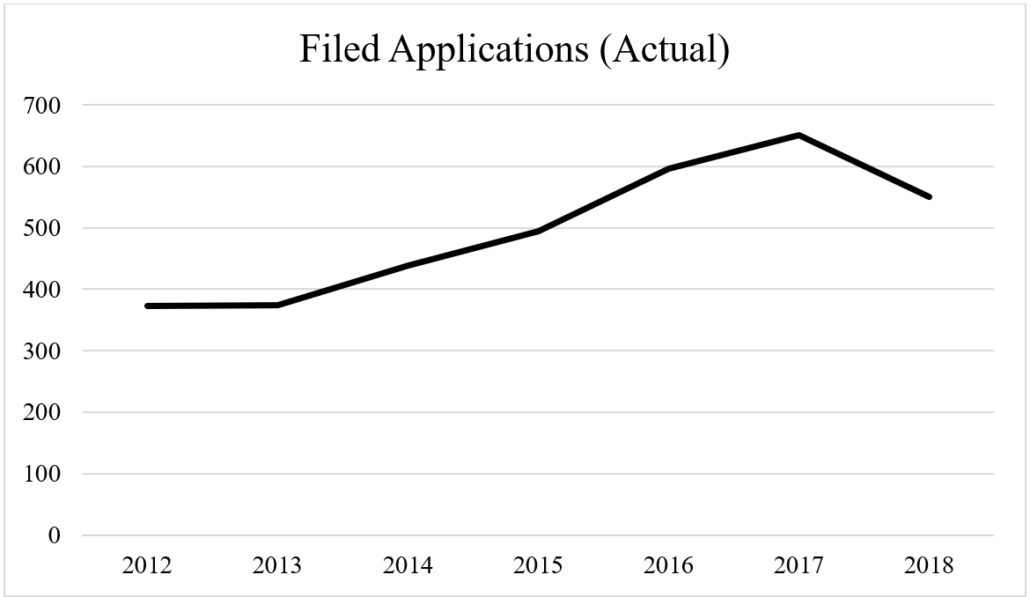

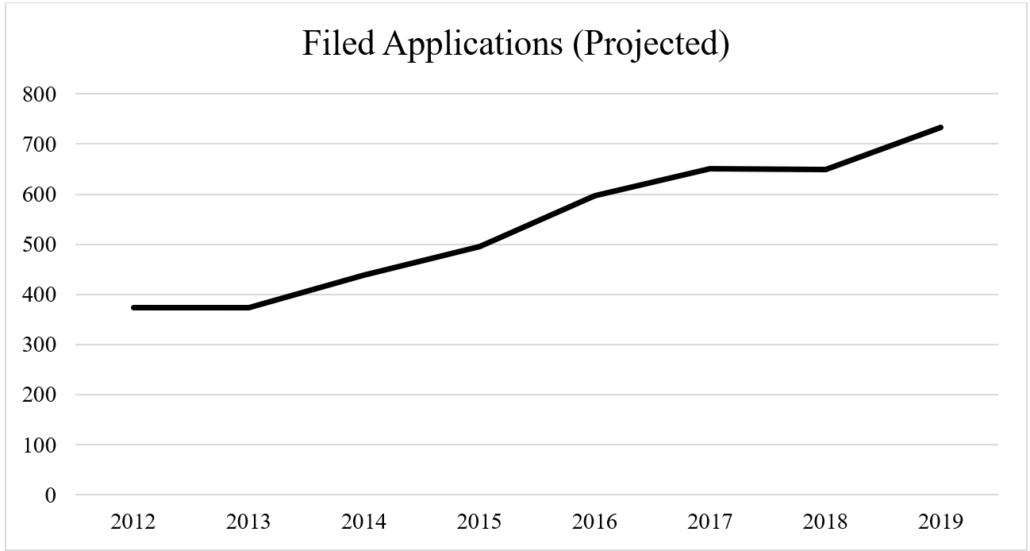

Because patent applications are generally not published until the earlier of issuance or 18 months following filing, publication trends are presumably delayed from filing trends. Therefore, it is useful to examine filing trends since 2012. Because of the 18-month delay prior to publication, data for any filings after July 1, 2018 are incomplete as such applications may not have been published. Therefore, both actual values from 2012 through 2018 and projected values for the years 2018 and 2019 are provided below. Using actual filings from 2017, there has been a 75% increase in filing activity since 2012. Using the projected filings for 2019, there has been a 96% increase in filing activity since 2012. The following charts demonstrate the increase in filing of cannabis-related patents since 2012 based on application filing date information.

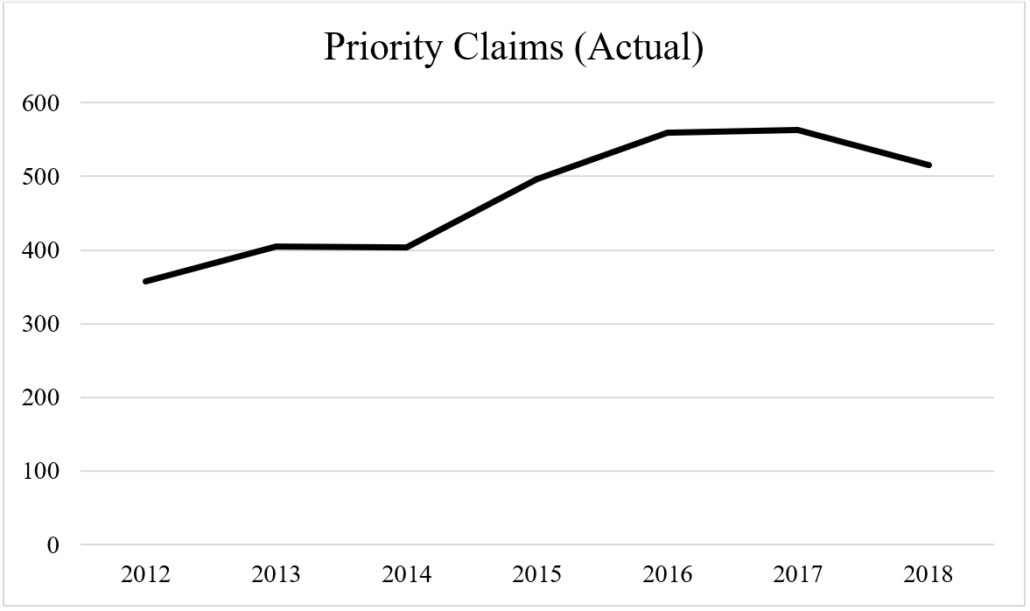

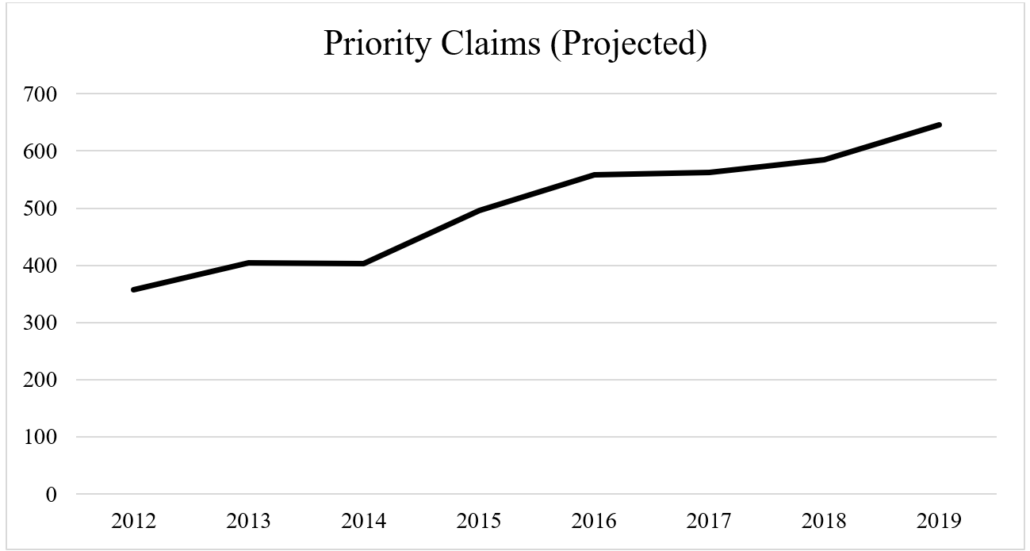

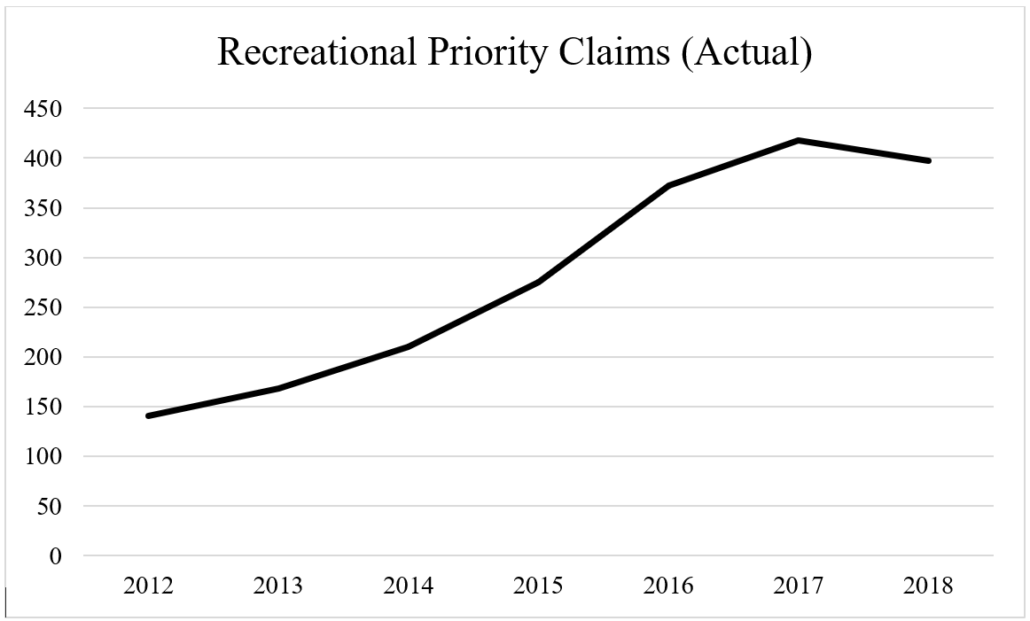

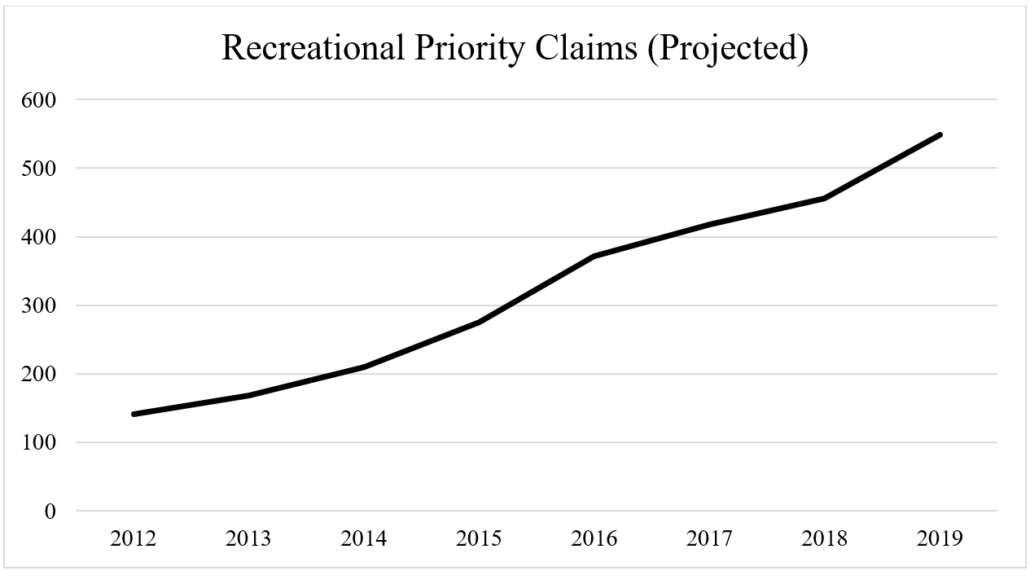

The AIA transitioned the United State patent system into a first inventor to file system, which is expected to encourage the early filing of provisional applications to secure priority rights. Provisional applications are not published and therefore do not contribute to the publication or filing data above. However, provisional filing activity can be inferred by looking at the claimed priority dates for published applications and issued patents. While the AIA did not fully take effect until March 2013, data are presented since 2012 for ease of comparison with other metrics in this report. Due to incomplete data for 2018 and 2019 as noted above, both actual and projected values are provided. Using actual priority claims for 2017, there has been a 58% increase in provisional filing activity since 2012. Using projected priority claims for 2019, there has been an 80% increase in provisional filing activity since 2012. The following charts demonstrate filing trends based on claimed priority date of the application.

Hemp as a Distinguishing Factor

Hemp has generally enjoyed more acceptance for its industrial uses than marijuana, despite the fact that both constitute cannabis. Inclusion of hemp is necessary to return all results for cannabis related patents. However, to provide a better picture of post-2012 activity in the recreational market, a separate set of searches was performed omitting “hemp” as a search term. It is presumed that doing so will return patents and applications that are more focused on the recreational or medicinal cannabis market. This is based on the fact that many of the results obtained through searching “hemp” include inventions with industrial applications, such as plant fiber composites or textiles, rather than inventions related to personal use of cannabis. For convenience, such patents are referred to as “recreational.” Because this method of discriminating does not perfectly correlate with the subject of any given patent, the results pertaining to the recreational market represent general trends rather than exact activity. Nonetheless, the trends are worth noting for an evolving industry.

“Recreational” Patent Trends

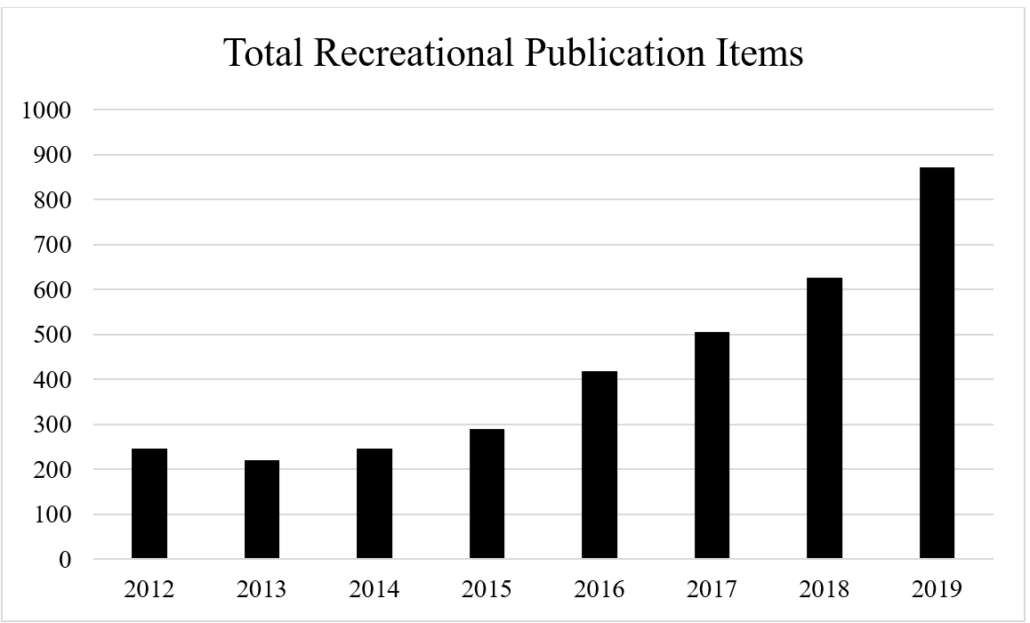

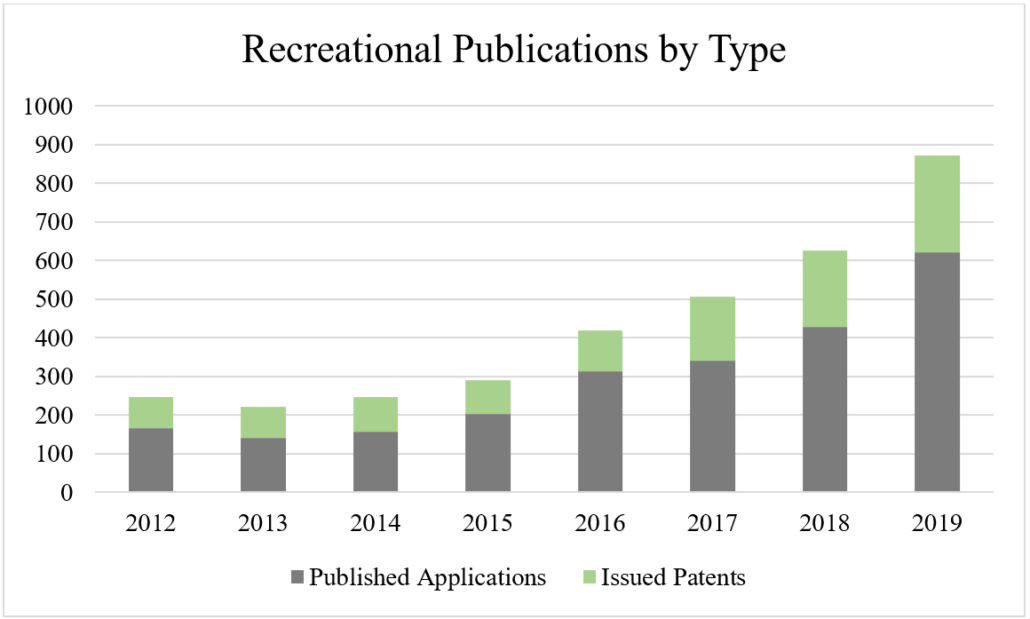

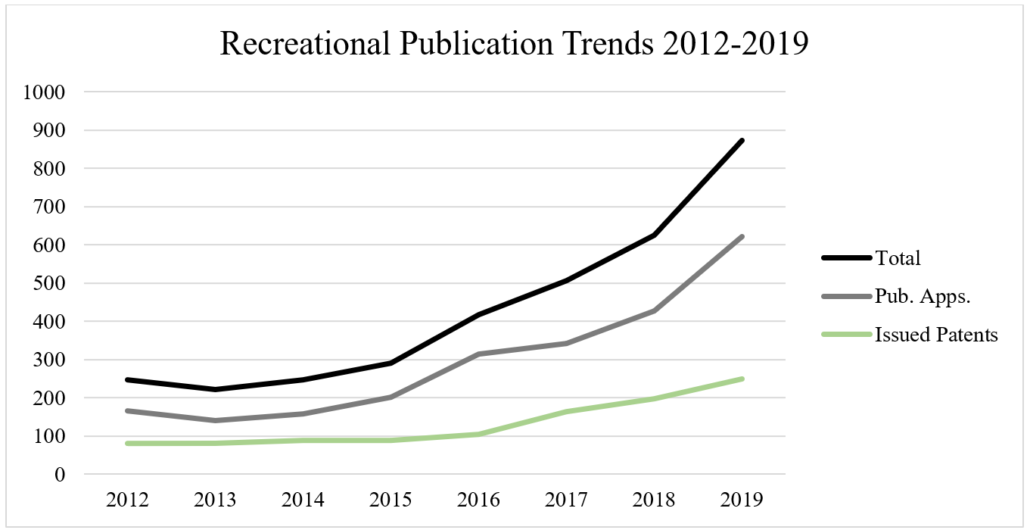

Between 2000 and the end of 2011, the USPTO published 2115 documents associated with recreational cannabis inventions. This number consisted of 1623 published applications and 492 issued patents. Between 2012 and the end of 2019, the USPTO published 3427 documents associated with recreational cannabis inventions, consisting of 2373 published applications and 1054 issued patents. This represents 62% more total documents in 2012-2019 compared with 2000-2011. Total publications increased year-over-year since 2012, with a 253% increase between 2012 and 2019. Published applications saw an increase of 275% over that period, with issued patents seeing a 209% increase. The charts below demonstrate this trend.

These findings correspond to the overall increase in cannabis-related patents and demonstrate that the recreational patent sector is growing at an even greater rate than cannabis patents generally. This supports the theory that recreational markets and expansion of legal personal use of cannabis have resulted in an increase in patent activity in the industry.

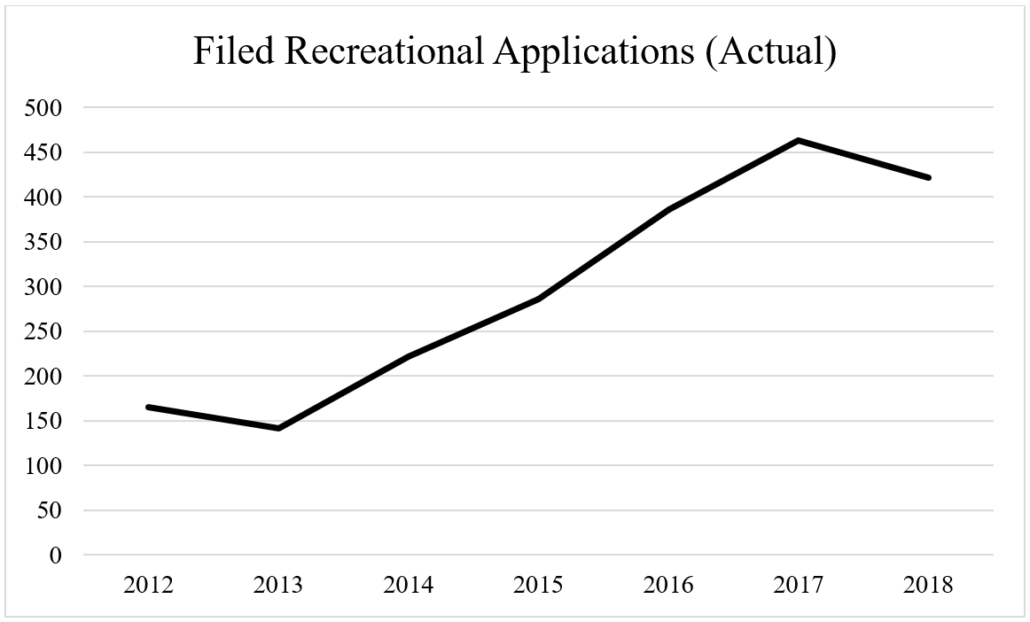

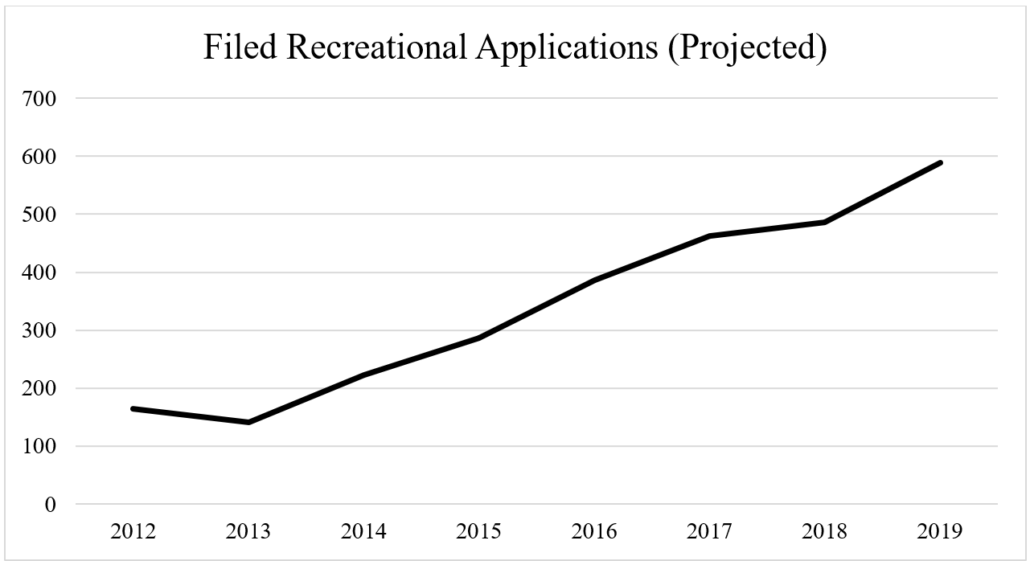

Again, publication totals are not necessarily the most accurate reflection of patent behavior by cannabis businesses. Therefore, it is useful to examine filing and provisional trends for recreational patents. These results are subject to the same 18-month delay problems noted above, and therefore actual and projected values are provided. Using actual filing data for 2017, there has been a 181% increase in filing activity since 2012. Using projected filing data for 2019, there has been a 257% increase in recreational filing activity since 2012. Using actual priority claims for 2017, there has been a 196% increase in provisional filing activity since 2012. Using projected priority claims for 2019, there has been a 289% increase in recreational provisional filing activity since 2012. The following charts demonstrate recreational filing trends from 2012 to 2019.

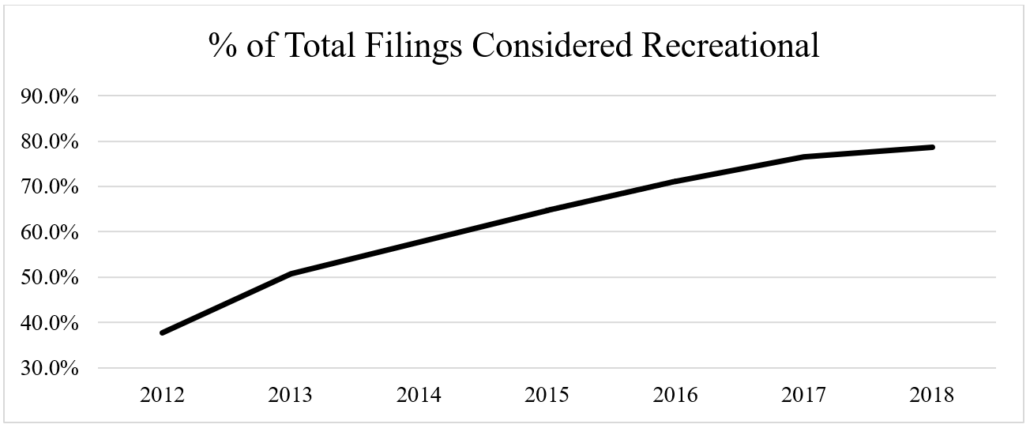

Patents that could be classified as recreational made up approximately 53% of all filings between 2000 and 2011. However, following legalization the percent of patents and applications considered recreational has increased to approximately 77% of filings in 2018. The chart below demonstrates the growth of the recreational sector’s share of cannabis patent activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the data provide clear evidence that cannabis patent activity has increased over the last decade. Further, patents associated with the recreational and medicinal sectors of the cannabis industry appear to be increasing at an even greater rate.

Further Developments to Watch

The trends demonstrated in the data suggest that cannabis patent activity will continue to increase in 2020 and beyond. This is further expected due to continued legalization efforts. It remains to be seen whether the federal legalization of industrial hemp and implementation of USDA plans will result in the recreational sector’s share of patent activity decreasing, as activity becomes focused on industrial hemp related patents.

An additional area that merits investigation is the issuance rate of cannabis patents. A rudimentary estimate comparing the number of filings to the number of issued patents for 2012-2019 yields an issue rate of approximately 49.6%. Assuming an average time to issuance of 2.5 years, comparing the total filings from 2012-2017 with the total issued patents from 2012-2019 yields an issue rate of approximately 64%. Comparing the total filings from 2012-2017 with the total issued patents from 2014-2019 yields an issue rate of approximately 52%. The issue rates for recreational patents over the same timeframes are similar. However, given the wide variance in time between filing and issuance, the above rates are only speculative. There has been concern that cannabis patents are issued at a higher rate due to the lack of prior art in the field which examiners can cite against the issuance of a patent. The issuance rates noted above do not seem to lend much support to this concern, as the USPTO claims its overall issuance rate is roughly 68%.

Other concerns have been raised about the strength and usefulness of cannabis patents. It is currently unclear how many issued patents are strong enough to survive challenges of invalidity in either post-grant USPTO proceedings or litigation. Currently, only one major cannabis patent is in litigation.[1] As of this writing, the court appears to be treating the case as any other patent infringement suit.[2] However, industry participants will surely watch the case and its outcome may affect the perceived value of cannabis patents and subsequently alter patent activity.

About the Author

Ian Johnson is a registered patent agent with Plant & Planet Law Firm He works with clients to obtain patents and other protection for their intellectual property and assists clients in licensing, acquisitions, and sales of valuable business assets. He also draws on his experience as an entrepreneur and his broad background across technology, business, and law to support Plant & Planet Law Firm in providing holistic solutions on matters related to business entity formation, corporate governance, and investor relationships. Ian holds a Bachelor of Science in Engineering with a concentration in acoustics from Purdue University. He anticipates receiving his J.D. from the University of Florida Fredric G. Levin College of Law in May 2020. He can be reached at ijohnson@pnplf.com.

Plant & Planet Law Firm was founded with a mission to provide legal services to clients whose research, technologies, products, innovations and businesses make the world a better place. The firm leverages its professionals’ variety of legal and technical backgrounds to provide clients solutions in the areas of intellectual property, business law, international law and commerce, and more. The firm is proud of its involvement in the emerging legal cannabis industry, and is also heavily involved in the agriculture, water, clean energy, life sciences, and medicine industries. Plant & Planet is a trusted home for inventors, entrepreneurs, and companies looking to improve the world. All the firm’s activities are tied to its mission statement: “Our clients make the planet better.”

[1] United Cannabis Corp. v. Pure Hemp Collective Inc., No. 1:18-CV-01922 (D. Colorado filed July 30, 2018).

[2] United Cannabis Corp. v. Pure Hemp Collective Inc., No. 18-CV-1922-WJM-NYW, 2019 WL 1651846 (D. Colo. Apr. 17, 2019) (Order Denying Defendant’s Early Motion for Partial Summary Judgment). Discovery in the case is ongoing at the time of this report.

DISCLAIMER: This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is created by this report. Neither the author nor Plant & Planet Law Firm will be liable for any harm arising from actions taken in reliance on any information herein.