Although I have degrees in botany and plant genetics and have worked with plant breeders for 20+ years, I recently learned that I have been sloppy in my use of plant-breeding terminology. Part of that comes from the fact that the truly geeky among us (the professors who make the rules) sometimes change the rules without telling the rest of us. Part of it just comes from learning by hearing, rather than digging-in and looking up the actual rules. Which, being a lawyer, is something I would never do in other parts of my job. So this post is my effort to clean up my act as far as terminology goes, and to provide an update to anyone else who has questions about these things.

If you already know this, please skip to any other blog post on this site. This is going to be way too basic for you. But since I’m quite fascinated by how much sense this terminology makes, and also by the fact that I didn’t fully appreciate it until now, I’m going to “geek out” on it here. So read on, or click back to more interesting topics, as you will.

Cultivar is Most Correct, but Why?

Let’s start with the “right” word: cultivar. It is a portmanteau or, as my kids would call it, a mashup, of the words “cultivated variety.” A cultivar is a group of cultivated plants that all share the same character or characters that are consistently inherited within the group. This means that the cultivar is defined by the phenotype, and not specifically by the genotype. In other words,

a cultivar is a sort of functional grouping of plants based upon the fact that they fit a certain criterion—the trait or traits the breeder was looking for in selecting the cultivar in the first place.

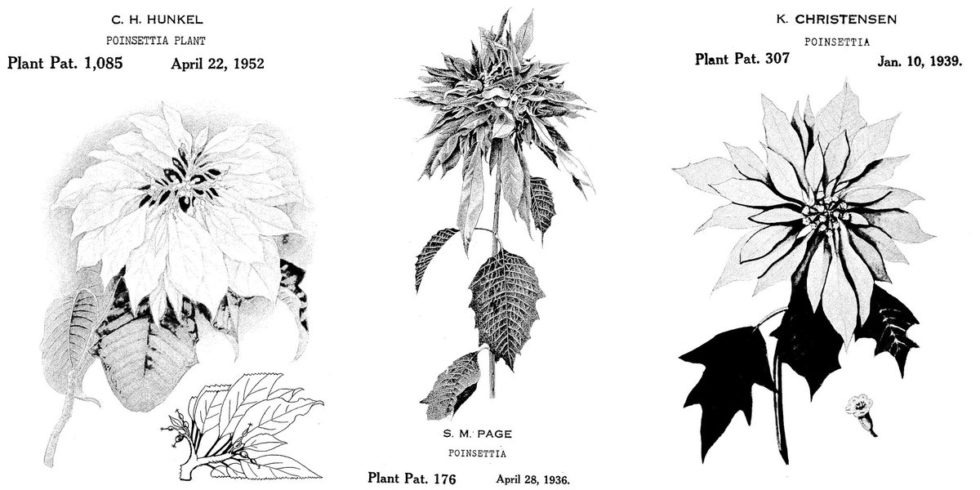

To obtain and stably maintain important traits in some plants, it is necessary to identify a single plant with those traits and then make exact genetic copies, via cloning. In such cases, the cultivar can only be one that is genotypically uniform. All members of the cultivar are genetically identical. This is the case with cultivars or “varieties” of grapevines and fruit trees, for example. They are asexually propagated and, to put them into the context of other posts on this site, are protected by plant patents. To read more about plant patents, click here.

However, in other plants, the traits that matter in defining the cultivated variety—the cultivar—can be heritable via sexual reproduction. In those cases, essentially all of the seeds produced by a certain event, whether that event is a self-pollination, an open pollination, an F1 hybridization of specific parents, etc., produce plants that display the cultivar-defining traits.

Of course, this makes sense because it is utterly impractical to propagate some plants asexually, and yet these seed-propagated plants are bred, selected, and cultivated to obtain certain desirable traits. Familiar examples of seed-propagated plants are the grains like wheat and rice. IP protection for most seed-propagated plants is available in the U.S. through the USDA Plant Variety Protection (PVP) system. While USDA PVP protection is not currently available for Cannabis cultivars, this post explains what can be done to protect seed-propagated cultivars, cost-effectively, with U.S. patents.

Some plants, like Cannabis and turfgrasses, are propagated both via seeds and by cloning. For example, some Cannabis cultivars have traits that are uniform enough to be seed-propagated and other Cannabis cultivars require clonal propagation to maintain their key traits. This fact demonstrates why it was important to come up with a an inclusive term, like cultivar, that would cover both situations—cultivated varieties phenotypically “uniform enough” for commercial purposes, whether those varieties happened to be genotypically uniform or not. However the cultivation and selection is done, and whatever traits collectively are important enough to define the cultivated variety, that set of traits, uniformly inherited, defines the cultivar.

Varieties Can Be Naturally-Occurring

Now on to the term “variety,” which is conceptually part of the more preferred term “cultivar.” Variety is just a less-specific term, because there can be naturally-occurring varieties as well as cultivated varieties. Nonetheless, it is often used interchangeably with cultivar, probably because in the context of commercial plants and plant breeding, it is implicit that a variety under discussion would be a cultivated one. Even official legislative documents like the Plant Variety Protection Act use the term. So it’s not an incorrect term, just more inclusive than would be ideal, inasmuch as it brings in certain varieties that were of natural origin and, therefore, should not be the subject of intellectual-property protection. The plant varieties produced by nature are and always should remain part of the public domain.

Strain Has No Accepted Meaning

What about the term “strain,” and where does it fit? The term strain appears to be used most often and most correctly in connection with microbes and viruses, and more informally in reference to plants and rodents. In plants it has no official meaning but generally applies to the group of offspring that are descended from a modified plant. I think the main reason people tend to use the term in some situations is because they may receive a sample—some seeds or an individual plant—from someone else. They maintain it through some generations and may keep using the same name as the strain they were given. Or they may give it a new name to reflect any changes that they selected for or that they may just have observed while in their care. Since there is either no need or no formal process for naming or registering this particular genetic line, the strain name they give it is enough. So they refer to it as a strain, just to avoid appearing to elevate the name to some higher level of official evaluation or importance. It seems to be essentially a default status. Kind of a common-law variety or cultivar, so to speak.

This usage appears much more common in Cannabis than in other plants I have worked with. My guess is that this is because Cannabis breeders have not been as involved in the out-in-the-open cultivar development and naming and intellectual-property protection process as breeders of other plants. So maybe it will take a while for the Cannabis community to move from “strain” to “cultivar,” or maybe it will remain a part of the idiom of the industry.

Regardless of whether there is ever a uniform adoption of the term “cultivar” in the Cannabis industry, it’s at least interesting (well, maybe only to me) to understand the extent to which the terms “cultivar,” “variety,” and “strain” overlap, how their usage may have originated, and why the usage might persist. And, now that you have read all the way to end of this post, welcome to the terminology-geek club.

By Dale Hunt – The opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of his professional colleagues or his clients. Nothing in this post should be construed as legal advice. Meaningful legal advice can only be provided by taking into consideration specific facts in view of the relevant law.

Special thanks to TeePublic.com for use of the image at the top of this post.

Hi,

Thanks for the interesting information.

How do you think this will play out in the cannabis industry?

Will some companies obtain patents which make commercial sales of certain clone strains illegal? Strains which have been in circulation for some time already?

Is a company able to patent their clone strain using cannabinoid profile, genetic makeup, and traits as the basis and will this be speficic enough to serve the needs of the cannabis community? If the answer is no do you believe we ahoukd be trying to change cannabis plant law?

Thank you

Hi Josh,

I may have replied offline already–it was a busy time when you posted your comment. If not, I apologize. But even if I did, I’ll reply here in more detail because this is a great comment and raises issues that are worth addressing.

If a company tries to patent some sort of subject matter broad enough to encompass strains or cultivars that are already in circulation, rendering them illegal in some way, it would be against public policy. (Some will scoff at a statement like that, because it seems like so many things that Big Ag does are against public policy, or should be, right?) But public policy when it comes to patenting is very focused on not letting a new patent take something out of the public domain that is already in it.

New patents need to claim NEW subject matter. If they reach broadly enough to cover things that are already “out there” then their claims are–by definition–not new and therefore not patentable. Sometimes claims like that still get allowed because patent examiners don’t always have the tools to find everything that is “out there” and within the scope of an over-broad claim. But when a patent owner tries to enforce an over-broad claim against someone by suing him or her, that defendant has an opportunity to assert a defense of invalidity, arguing that the patent was mistakenly granted. In a case like the one you’re describing, the easiest defense would be simply to show that the patent claims encompass cultivars/strains that were already known to the public before the filing date of the patent itself. That would be proof that the claims are not NEW, which is one of the requirements to get a patent in the first place.

The only way a company should be able to patent according to chemotype as you described is if that company could genuinely show that the chemotype they are claiming met all of the requirements of the patent statute. Meaning that they could show that the “new” chemotype they were claiming were:

A. New (never before existed in any cultivar or strain anywhere ever)

B. Not obvious (not a trivial variation over any other known cultivar or strain)

C. Adequately described (the application provides enough detail that others of ordinary skill in the industry reading the application could replicate the invention from similar starting materials without undue experimentation, and in a similar range of variation in scope as is claimed – so if the applicant is claiming that this new chemotype is general and would block any other cannabis plant of any genetic background from ever having that chemotype, then the application should teach how to put that chemotype into any other cannabis genetic background WITHOUT UNDUE EXPERIMENTATION0 [SIDE NOTE: can anyone reading this even imagine all of the step-by-step breeding and selection and cultivation instructions that would be involved in meeting this statutory requirement, if someone were genuinely trying to claim a broad entitlement to a new CHEMOTYPE across a broad range of genetic backgrounds or even a narrower range of genetic backgrounds?]

D. Statutorily-permissible subject matter (not a product of nature, among other things – so demonstrate that this chemotype is not and has never been produced in nature)

So after considering that, we have to face a few questions:

1. Could a patent examiner who has to look for prior published documents as the basis to reject a patent application quickly run out of “tools” to reject a claim to a new chemotype? Yes, of course. Because who has been publishing a lot of detailed information about chemotype, until pretty recently, on databases that the patent office would have access to.

2. Could a patent examiner who never worked his or her whole life in the Cannabis industry and who therefore probably doesn’t fully appreciate the nuances of chemotype and maybe not the full complexities of Cannabis genetics fail to be stringent enough in holding an applicant to the standards about adequately describing the invention? Yes, of course. And this isn’t meant as a criticism of the examiners. Cannabis is a complicated plant with complicated genetics and physiology. I have 12 years worth of of plant science college degrees and I feel like I am still at the early stages of learning about how much there is to learn about Cannabis genetics and biochemistry and physiology and cultivation. Very early stages.

3. Finally, could a patent examiner therefore mistakenly grant a broad patent to a chemotype? Absolutely.

4. What is to be done about that? Be ready to defend whomever gets sued for infringing such a patent.

Wow, Josh, I think this is going to turn into at least one blog. Thanks for asking such a great questions. Cheers, Dale

I always used Cultivar for registered clones, variety for a landrace or seed variety, I never used strain.

I have 28 Cultivars of Cannabis with UPOV PBR or PVP protection, more than anyone else, my first in 1997 for Skunk #1.

awesome

https://waterfallmagazine.com

Wow! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a completely different subject

but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Excellent choice

of colors!